Are you prepared for the changing landscape 2024 will bring? Is your business sustainable, agile, and profitable? Set your business’s foundations for success this year. I brought Luke Holman to the B2B Go To Market Leaders Podcast to learn how.

Luke is a serial entrepreneur and current Chief Innovation Officer of Applied Frameworks. He shares his expertise on agile business methodologies, pricing and packaging strategies, and the 3 Pillars of Business Sustainability. Gain valuable insights into the art of client outreach, strategic pivots, and the influential role of a profit-first approach in crafting successful go-to-market approaches. Fasten your seatbelts as Luke guides you on making our business more profitable, lasting, and flexible.—

Listen to the podcast here

Mastering Software Pricing: Innovation, Agile Business Tactics, and Profit-Driven Pricing with Luke Holman

The signature question: all my listeners love that I start the show, and we dive right into the meat of a topic, which is how do you view and define go-to-market?

Well, go-to-market is a set of comprehensive activities that help the organization take what they’ve created and bring it to their customers through any number of direct or indirect channels, any number of partner relationships, any number of sales team structures. Sometimes we have direct sales; sometimes we have indirect sales. We have sales reps; we have sales engineers. So, there’s a whole set of go-to-market activities that make sure that the organization is prepared to realize the benefit for themselves of what they’ve created for their customers.

Totally. I think you touched upon critical points, right? One is, obviously first and foremost, it starts with the customers whom you’re really targeting and who you’re solving for. That’s one, and then the intern aspect, you got the product team, you got the sales team, making sure that they’re aligned. Of course, you have a product, you have marketing, you have sales, and you have customer success, if it’s a software-as-a-service organization. So there are a lot of these teams that have to be aligned internally while bringing that product and taking it to a customer.

That’s right.

That’s a great start. So looking at your career journey and path, clearly, at least in the early phase of your career, you were very deep and very involved in the product development aspect of things. So we’ll dive into Agile practice. But just to expand and bring all our listeners up to speed? And can you share your career story like where you started? Why, what was your first job like what did you become and who you are today?

Well, I have had a long history in the technology field starting working for a very large company called Electronic Data Systems. And EDS had many, many data centers, and I was working in the technical area, literally crawling underneath the floor, cabling computers. I was working in network, networking, and then one thing led to another, and you get promoted; you become a developer. I picked up a bachelor’s and master’s degree in computer science and computer science and engineering from the University of Michigan. I went back to EDS, and I became a vice president of engineering at a subsidiary.

But there’s this journey in my career of always wanting to learn how to do and create and build the best products for our customers. So that journey led me through user interface design, and usability, but I actually ended up centering on product management, which is really trying to understand the needs of the customers as best you can and then build solutions that meet those needs in a way that creates a profit for the company.

In that journey, I became associated with the Agile software development movement, and at the very beginning helped form the first Agile conference way back in 2003, served on the board of the Agile Alliance, worked with the Scrum Alliance, have wrote several books, have started and sold companies have acquired companies. But in all of these areas, I’d say there was the foundation of Agile software development practices in Agile product management practices, all associated with creating a profitable solution.

Very cool. Definitely, we will get into the companies that you bought as well as the companies that you had a good exit. So, you did mention why you got fascinated and curious about agile and agile development and the Scrum process. So you did tie that back to how products get built and how they go to market and you’re really curious about the efficiencies and the gaps during the development process.

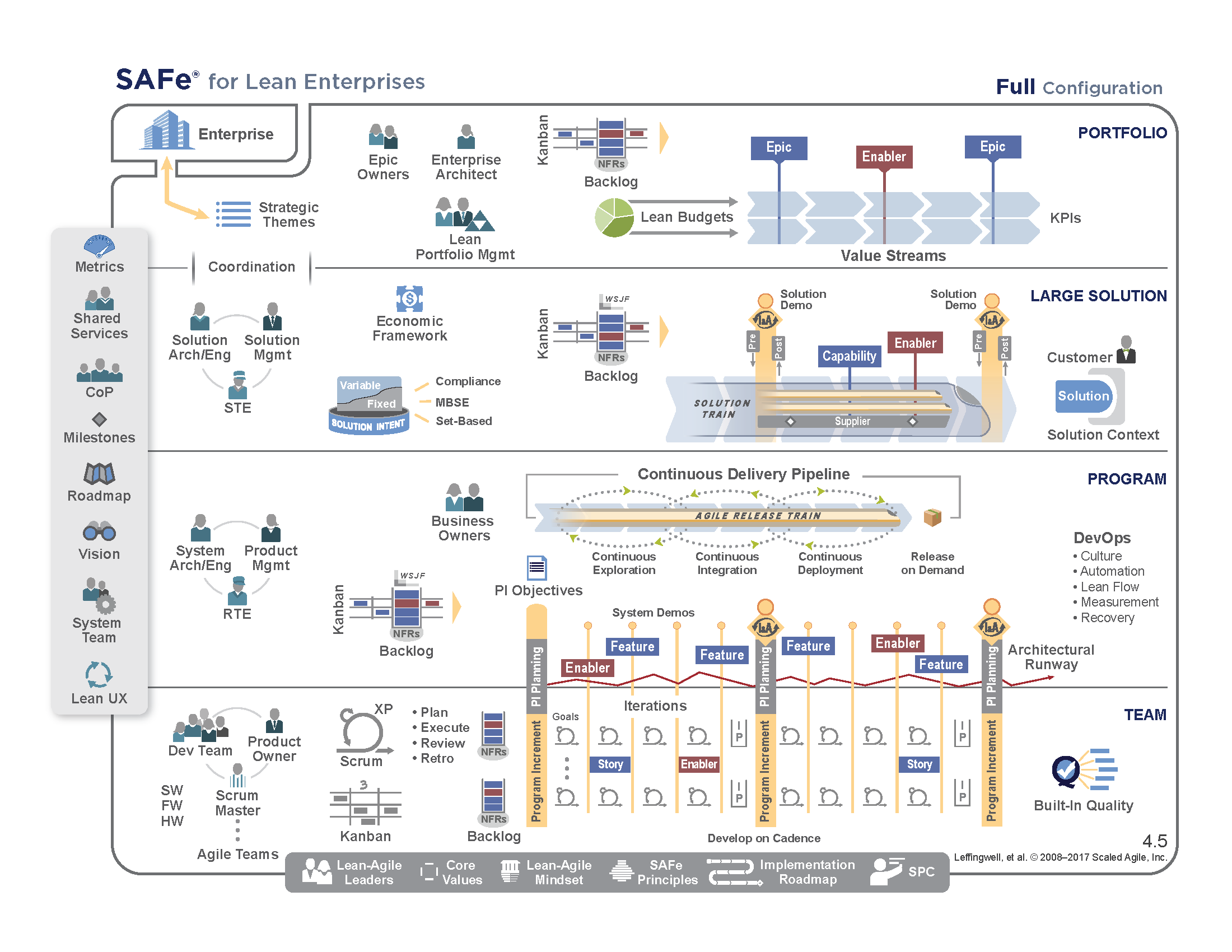

I wouldn’t equate at all Scrum with Agile. I would say that Agile is, according to the Agile Manifesto. Agile is a set of values and practices. There are many agile methods, Scrum being optimized for small organizations or a couple of teams in the Scaled Agile Framework, being by far the leading technique or method, optimized for large organizations or large numbers of teams. I have been more associated in my career and more aligned with large-scale development initiatives, with dozens of teams to hundreds of teams working on extremely large and complex systems.

And of course, I am a SAFe fellow, which is the highest distinction you can have in the SAFe community. I was a former SAFe contributor in both agile product management and in Lean portfolio management. So I’m more associated with the challenges of, in terms of a consulting capacity, the challenges of large organizations creating profitable solutions for myself, right? I’m an entrepreneur, and so my organizations are smaller. So I think it’s important to consider which of the two perspectives I’m being asked about.

One perspective is, how do you help large organizations with globally distributed teams work more efficiently? And also, for your own work? How have you created software companies? And then manage them? Because they’re slightly different forces? And sometimes radically different forces when you’re working with one or two teams versus say, 400 Teams? Right?

Scaling Agile with SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework)

For sure. And I would like you to share that expertise. I mean, as you well articulated it, look, when you’re building your own companies, you’re obviously small and nimble we’ll be applying one methodology versus when you work with the likes of just not to say that they are the clients, but the likes of large organizations like Google or HP or Cisco, or Microsoft, right? I mean, they have huge dev teams spread across the metrology that they will use for product development and delivery.

That’s right. So let’s go back to where you want to be if all you ever want to be as small and stay small, then a method like Scrum is probably fine. For me, I’ve worked in companies, and even in my own company, every family, every company has to have a way of making a financial decision. That’s portfolio management, whether it’s you and your partner, your pair bond partner, your wife, or your husband. If you were to sit down and make a financial decision of significance, like buying a home, or buying a car, or taking a family vacation or having a child, you would do it together. Similarly, when you’re a small company, you still have a portfolio because you’re still making significant decisions. And when you’re a large company, you’re making significant decisions.

So when people, when people equate significance with a dolllar amount, they devalue the kind of decision being made. So let’s say I’m Cisco, well, my decisions would be hundreds of millions of dollars. In terms of significance, right? That’s very different than the decision I would make at a small company. But both small and large companies have significant decisions to make about how they invest their money, how they spend their money, and where they put their attention.

No, totally. I think you hit it correctly. The significance does not or does not correlate or equal to the size of the business. But the significance matters, right? For example, my own journey – when I work at startups or for my own consulting company, as we sit today this week, I was figuring out where I should invest my time, energy, and money. Should I pursue a different go-to-market strategy? Should I invest in building a new content portfolio that will be relevant for demand gen and demand creation? Or should I work with a co-founder friend of mine where we know for a fact that I’m blacking out the AI compliance space? A lot is happening in that space. Is that the right investment area?

Yeah. Absolutely.

And then the scale of the decision-making and the factors will go many for like 5-10X when you talk about companies like Cisco and Microsoft, right? So, you are the founder and CEO of Conteneo. Was it a consulting practice or a software product company or both? What is that journey like?

Well, most companies are a mix of both. Most companies have some kind of a service component. It’s just the degree. I mean, some absolutely pure software companies don’t. But most companies, as they grow and evolve, have a services component. Conteneo was based on my book “Innovation Games.” What Conteneo provided were software platforms for doing games online and consulting services that would help organizations design and produce both in-person and online innovation games events. So, in the Agile community, there are many well-known games like Sailboat or Speedboat, product box by a feature. All of these games have an in-person expression, and many of them have an online expression. So Conteneo was a bootstrapped company in the B2B software space where we provided to our customers a platform for doing innovation games with distributed teams and in an online setting. We bootstrapped it. So we didn’t have outside VC funding, which is a little rare in Silicon Valley. And then we ended up selling Conteneo to Scaled Agile a few years ago. And that was a great outcome for all stakeholders.

Innovation Games by Luke Hohmann

And again, as this is a go-to-market podcast, it’d be good if you can, at least at a high level, talk about your go-to-market journey, but continue, like early days to how you scale it and the exit?

Well, there are many aspects. I think the question is, to what degree does a given company consider its marketing strategy a go-to-market strategy? I consider that many times the marketing strategy is intimately related to the go-to-market strategy. So we followed a pattern that’s somewhat successful in business where we wrote a book, we built training. The book creates awareness and interest in the training. The training teaches people how to use the techniques, and it creates demand for consulting services and online platforms. Once we had the online platforms, we were able to serve the demand that we had created. In terms of a go-to-market strategy, that’s where I think you start to see the distinctions between how you intend to go to market and then the feedback from going to market.

Let me explain one of the pivots that we made at Conteneo. We’ve been talking about innovation games, which is a discrete event of usually between four and eight people; they can come together and work together on a business problem. Well, we thought the right way to price that was per game, because you can think about the unit of value being a game, right? What happened was that it created a variable spend, and our customers didn’t like variable spend, especially when so much of what we do in business now is a monthly fee. You have a fixed monthly fee, but you have variable usage; sometimes you’re using the platform more, and sometimes you’re using the platform less. So we found that in our go-to-market strategy, we were charging the right amount of money, but we weren’t charging the right way for the money. That’s the kind of go-to-market change that people need to be aware of. We call that a value exchange model. In our new book, “Software Profit Streams: A Guide to Designing Sustainably Profitable Businesses,” we talked about, as part of your go-to-market strategy, you have to get your pricing, packaging, and licensing down, and there are choices that you need to make as a product manager, as a product team. How do I trade money for value? The value exchange model needs to be aligned with how the customers both perceive value and how they want to pay for value. Those were some of the changes that we made in our own go-to-market strategy and our own go-to-market journey.

Software Profit Streams by Jason Tanner & Luke Hohmann

The brilliance that stands out in your go-to-market journey is you touched upon a very key aspect. I’ve studied go-to-market leaders, understanding what sets them apart. Think of the NBA League, with 30 teams. However, something magical happens when you peek under the hood of the operations of the top two or three basketball teams consistently making it to the playoffs and winning titles. It comes down to two or three things.

So, concerning go-to-market teams, it boils down to content, community, and experiences/events. Three crucial elements. One aspect you’ve nailed very well is content, exemplified by the book in your case. The innovation games in your earlier company, and now focusing on software pricing. What led you to that thought process? First, creating and writing a book. Then, deriving training material, followed by consulting and software development. What influenced you to embark on this path?

That’s a no. No one’s ever asked me that before. So, that’s a really interesting question. I learned the power of writing a book when I first moved to Silicon Valley. My first company in Silicon Valley was a company called Origin Systems. Origin Systems was an absolute breakthrough company. It was wildly innovative. What we did was take all of the world’s patent data and put it into a data warehouse for analytics. In terms of the utility of a patent, how does a patent get monetized? What is the patent related to? What are the opportunities for innovation? It was based on the work of a couple of gentlemen, most notably a gentleman named Kevin Rivette. I remember when I joined the company, the head of marketing was a guy named David Polio. That’s where I learned this pattern. David, in one of our leadership meetings, said, ‘Hey, when you’re creating an entirely new industry, an entirely new thing, you have to get the content first. The way you get the content first is you write a book.’ So Kevin Rivette wrote a book called ‘Rembrandt’s in the Attic,’ which was considered a breakthrough and groundbreaking book associated with intellectual property licensing. That book, in combination with our software platform, really drove that company to a successful outcome. I credit David Pulizia with showing the power of content and then building out the community and the software platform. At Origin, we didn’t have a lot of events, but we had a great software platform. I think, Vijay, the notion of the content is partially correlated to the degree of innovation or the degree of novelty about what you’re offering.

When I wrote ‘Innovation Games,’ it was the first book in the genre of using serious games, serious game techniques, and collaborative games to solve problems. Since then, we’ve had other books like ‘Game Storming’ or ‘Reality is Broken’ from Jane McGonigal. But when you’re the first one, you really need to create that content to cement the industry and the breakthrough. That’s why we did that with ‘Software Profit Streams,’ the new book. There are books about pricing, but the problem with books about pricing is that they’re pricing pens and menu items in restaurants and wine.

You know, consumer products pricing.

Even in the business world, pricing gets wrapped up into things like supply chains and Bill of Materials, which are all important. But software is so different that we decided the prior work was no longer sufficient to meet the needs of what’s happening in the world. Andreessen is right; software is eating the world. We need a means by which we can look at pricing, packaging, and licensing for software-enabled solutions because those are unique in the world. We needed something new to really capture that.

Well said, and clearly, you learned your lessons, and you got the playbook. Going back to what you mentioned about Origin Systems, you really learned that system from your head of marketing back then. And you apply that in your own consulting career.

He’s brilliant. And, I think it’s a consistent pattern. We’re not the only firm that applies that pattern. But there’s enough proven success around that pattern that we should look at that.

Absolutely. So, did you take the time to write the book first, launch it, and then start the consulting practice and the training, or what is…

The book was mostly informed by years of consulting experience. We were able to mine the experience of ourselves and our customers, really looking at all the different work we had done over a near 20-year history. Applied Frameworks has been around for more than 20 years, so we had a very rich and deep history to draw from as we were writing the book. Now that the book has been written, we’re working on the software platform called Horizon and have it in the market. Now we’re just following good agile practices, continuing to improve the Horizon platform for solution profitability management.

Fantastic. So one of the questions I typically ask my guests, and I do that more in the latter part of the show, but clearly, when it comes to you. So one of the questions I ask is, what is our special secret sauce? And what should people come to you for advice? Clearly, in your case, it sounds like you’ve mastered the game around go-to-market, in terms of content, sequencing, and applying Agile and Scrum practices. That’s how I see it.

I think I would add that I would be cautious, again, about, for example, we’re not a sales training company. The art of go-to-market is treating your sales team. Our expertise is in pricing, packaging, and licensing. For example, too many organizations try to get to a good, better, best pricing model when sometimes good, better, best pricing isn’t needed. Other problems we see are companies, especially large companies, will create a solution. Then they deliver more value using Agile techniques, but they don’t raise the price, or they don’t have a strategy of how their solution architecture captures value. We see applications just get bigger and bigger. Sometimes the better approach is to keep the main application tight and focused. Then add modules or add-ons that an organization can acquire to enhance their offering. It’s really that strategy that you’re looking for that will help you determine your actual price point and how to make the most amount of money at it.

I’m looking at your book, the Software Profit Streams book. And as with any top-tier books, you would also provide a canvas. Can you walk us through the canvas for the profit stream? Absolutely.

So canvases are powerful tools; we have the business model canvas and the profit-sharing canvas. What a canvas does is it allows us to quickly and effectively capture the main elements of a causal system. I’m an engineer, you’re an engineer; we have an engineering background and think in terms of systems. When I deal with pricing, I have to manage three really related items. First, I have to manage my solution sustainability. What are the needs of my customer? What does my solution provide to my customer? How are they evolving over time? Because customers are not static, and problems in the world aren’t static. I have to have an ongoing evolution, a roadmap, etc. The second kind of sustainability is economic sustainability. Does my customer feel they’re getting good value, which is more value than what they paid? Am I creating a sustainable business? Am I making a profit? Is my revenue greater than my costs? The third element of sustainability is what we call relationship sustainability. There are really three relationships that matter for a software-enabled solution or a company. The first is my suppliers. Everyone is licensed in various technology components. How am I managing my in-licenses and my relationship with my suppliers? The second is my relationship with my customers. Software isn’t sold; software is licensed. There’s a license agreement, terms of service for a website, or a complex agreement for traditional software that defines my use of that software. What are the terms, conditions, and entitlements? How am I managing my relationship with my customers? The third component is compliance, which concerns how am I managing my relationship with regulatory agencies, and with standards? Let’s say that you and I wanted to build a website together, and we wanted to make it accessible to people with disabilities. Well, now I have to honor the WC3 web accessibility standards. It’s not a law, but it’s a choice that I’ve made. When we look at compliance, we’re thinking about laws and regulations ranging from, say, GDPR or the Australian Privacy Rights Act or in California, the CCPA, to standards and agreements. How I manage my relationships determines my relationship sustainability. If I routinely create poor relationships, it’s going to be hard for my business to continue to grow and be successful.

I think that’s a good canvas. I’m definitely going to refer to that, and I’ll highly encourage other listeners to go check out the book ‘Software Profit Streams‘ in terms of pricing and packaging. Perfect. Wonderful. Quick note, this is the end of part one. So if you can just click on the link and join the second one. To my production team, that’s the end of part one. I’ll see you on the other side. Great. So yes, I think you’ve shared a great framework there when it comes to pricing and packaging. Switching gears a bit over here. Obviously, as you and I know, go-to-market, there are so many flavors. You will see successes, you will see failures. It’s not always up and to the right. So if you can share either from your own personal experience or working with the various clients that you have, a go-to-market success story and a go-to-market failure story. That’d be great.

Sure, well, for a go-to-market success story, one of my clients is CVS Health. They had an extraordinary go-to-market success story with the introduction of their app for scheduling COVID-19 vaccines. It was created in a time of crisis, so people were stressed. It was rolled out in record time for a large company—a very complex app when you think about scheduling for a vaccine with 1000s of stores across the United States, geolocation, capacity planning, store hours, and a tremendous amount of logistics and data. From a go-to-market standpoint, they were able to create and deliver that app. In this case, pricing and packaging were not relevant because it was free. But in terms of a go-to-market success story, that would be one of them. Another one related to our work in pricing and packaging is a company called Knowify. Knowify creates construction management and billing software. When we started working with them, they hadn’t adjusted their pricing and packaging for a couple of years. They had been successful, but we got involved because they just got a post-seed funding round from a venture capital firm, Companion Ventures. Applied Frameworks works with venture capital firms and private equity firms to improve the pricing and packaging aspects of their portfolio companies. One thing we worked on with Knowify was changing their packaging. Before our work, about 20% of their customers signed up for the annual plan. After adjustments, we got that number up to 60%, improving cash flow and making it easier for their sales team to guide customers through changes. It was an amazing change for their go-to-market process and approach from a pricing change.

Fantastic, a great story, and great success stories for both. So, I’ll click on each of them. CVS, you mentioned obviously it happened in the time of crisis, the COVID pandemic scenario. So what prompted CVS to reach out to you? I’m assuming they reached out to you, and who from CVS did that? And why?

Fantastic, a great story, and great success stories for both. So, I’ll click on each of them. CVS, you mentioned obviously it happened in the time of crisis, the COVID pandemic scenario. So what prompted CVS to reach out to you? I’m assuming they reached out to you, and who from CVS did that? And why?

Sure. So we had a prior relationship, as in so many arenas, with their head of Agile. They reached out to us as part of our normal relationship, doing agile work and scaling agile. In the case of Knowify, the outreach was initially from the venture capital firm that made the investment. Companion Ventures made the investment and then told Knowify, ‘Hey, you should work with Applied Frameworks to improve your pricing and packaging.’ Usually, in this kind of world, you’re going to see word-of-mouth referrals, etc., which is still a significant part of the business.

I think that is a smart move, obviously, on your side to work with influencers. In the first case, it was the head of HR at CVS, a good relationship over the years. In the second case, it was the venture capital that influenced it for sure.

Now, of course, as our software package becomes more prominent, we’re doing more traditional go-to-market strategies, like webinars and podcasts. Also, advertising, blogs, and normal content optimization, content generation. Those are all parts of the go-to-market mix. It’s important for people to remember that when you’re smaller, your go-to-market strategy might be more intimate. When you’re larger, your go-to-market strategy might be more volume-based with less intimacy. Either is probably right; it’s just different. Go-to-market strategies and teams need different techniques and results.

Going back to the case study and success story of Knowify, you mentioned a great result where annual subscriptions increased from 20% to 60%. So what is the process like? Going back to our first question and our discussion, it’s about go-to-market. What is the go-to-market process? I would assume that you guys had to dig into and look at all the CRM records, the pricing, and so on, and the number of customers who did that, and then why people are not switching.

In the case of Knowify, we didn’t spend a lot of time, so I would say that you’re correct. In a normal case, you would be looking at your CRM data, looking at conversions, etc. In the case of Knowify, we were able to determine improvements through what we call a customer benefit analysis. We deconstructed their features into discrete benefits, reverse-engineered market segments, and repackaged the offering to better align with the needs of specific customers. So in the normal case, we would be looking at CRM data, win-loss data, and discount data, but in the case of Knowify, we had a strong signal through customer benefit analysis that we could change the packaging to better align with customer needs.

Fantastic. It’s great timing that you shared the story. I’m working with a client where we’re doing a positioning exercise. The positioning involves identifying target account characteristics, distinct capabilities, and features, and value themes. You got the account segments or characteristics, and features, and then you map them to hone in on the best fit, the 20% or 30% of customer segments that translate to 70-80% of the value stream for you.

We call that a solution benefit map. Once I know the benefits my customers are seeking, I can look at my features and the relationship between features, benefits, and the targeted segment. It’s a rigorous process but doesn’t take as long as it might sound. It can be done quickly when working with existing customers or companies with existing data

And then going to my earlier question, which is, yes, you’ve got go-to-market success stories. But I’m sure we all have go-to-market failure stories. Anything that comes to your mind from a go-to-market failure story?

Although, I think the question becomes if I have a go-to-market failure story, to what degree of failure am I talking about? The ultimate failure is when the company itself fails. So you could argue that it’s not a go-to-market failure; it’s just that it wasn’t a viable company. It’s harder to find go-to-market failures because if the solution is successful or if the company is successful, what that meant was they had a go-to-market experiment, and the explored experiment didn’t work. So they tried something else that did work. If we had persisted in trying to force the market to accept transactional pricing, the company would have failed. But we adapted, took the feedback, and adjusted how we worked. That’s pretty profound because go-to-market is like product-market fit. Sometimes people think, ‘Oh, I have product-market fit, and I’m done.’ But product-market fit is like getting on a highway; it’s the on-ramp. Once you’re on the highway, you have to constantly monitor and adjust your driving. You’re always doing micro-adjustments, and the faster you’re going, the more subtle and frequent the adjustment. Product-market fit and the initial go-to-market strategy get you on the highway, but after that, it’s a very strong repeat process of how am I doing, and how am I adjusting.

I think that’s a very good analogy. In my mind, as you’re speaking to that, it clearly shows that product-market fit is not once and done; beyond product-market fit, it’s scaling, tweaking, and iterating. Going back to your analogy, driving on the freeway, I have to constantly adjust to oncoming traffic, traffic ahead, change lanes, slow down, pivot—all these things apply to the go-to-market world. It reminds me of the conversation I had with Geoffrey Moore, who said exactly along the lines of what you mentioned—that there are not really failures; you either have success or learnings, and there are learnings even if the business fails.

Right, and even if the business fails, there’s learning associated with it. But it’s not clear that it’s a go-to-market failure. It could be just a failure as a business because it’s the right idea, but it’s too early for the market. We’ve seen that in the technology field where ideas get recycled. An example is the original idea for Uber and Lyft, patented about a decade before Uber got started. But the technology just didn’t exist at that time. As technology evolves, things that failed in the past become viable in the future.

Well said. I think that’s a great perspective. Going back to your favorite topics and how you built your businesses around Agile and pricing and packaging, and, of course, my favorite topic, product marketing. Typically, as seen and you can attest to this, it’s a combination of product management and product marketing that has to tackle these two areas. What have you seen, the challenges, as well as things that have really worked when it comes to product management and product marketing in these areas around Agile, thinking about prioritization delivery, and pricing and packaging?

Well, I think, Vijay, that the Agile community is a little better at working on the product marketing side because we do have this idea in Agile that I’m creating a constant flow of value to my customers. This is part of the Agile Manifesto. It’s the set of metrics that we track in SAFe is what we call the flow metrics. We look at things like how frequently are you getting value from your customers. And what’s your batch size? Are you taking on features that are about the right size, so you can continue to deliver value to your customers? The reason we wrote the book is that we’re getting agile organizations who are delivering a flow of value, but they’re not producing a flow of profit. Let’s think about this from the executive standpoint. Let’s pick any size company. Executives aren’t compensated for value. That doesn’t mean anything, especially in a public company. You’re not compensated for value; you’re compensated for creating a profit. And so what we’re seeing is a bit of a backlash in the Agile community, to be honest. And what I mean by a bit of a backlash is that you’re seeing, for example, Capital One firing hundreds of agile coaches and Scrum Masters. You’re seeing different companies say, “Look, we’ve been putting millions of dollars into agile in training, etc. And we need profit, especially with our macro economy. With high inflation, high inflation rates, high cost of capital, people need profit.” So what we’re saying is, let’s evolve. Let’s own proof. Let’s actually move from creating value to creating profit. Now, let me not talk abstractly, let me ask you some really basic questions. If I go to a company that’s doing Agile, I’ll ask them a simple question. They’ll say, “I don’t worry about your Agile process. Like, I don’t care if you’re using Scrum or less or SAFe, whatever, right? Last year, have you consistently delivered value to your customers?” And if they’re an agile organization, the answer is almost always yes, we are consistently delivering. And then I say, when was the last time you explicitly raised your pricing or you explicitly changed your packaging to make sure that the value you’re delivering is resulting in more revenue for your company? And it’s not as easy as answers. Many times, the response is, “Wow, we haven’t raised our pricing in eight months, 12 months, 24 months?” And I’m like, “Okay, you haven’t raised pricing in two years? Have you paid more people in salary and people?” Then I get the response, “Well, you don’t understand. Look, we’re growing as a company. And so we’re fine.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but you’re not. No one can grow indefinitely, right? There’s always some limit to the size of the market. And you want to condition your customers that when you’re creating more value for them, you’re gonna get more value back.

So two things come to my mind when you say that. One, it took me back in time to my MBA days, when my marketing professor said one thing, which really stuck in my mind, even to this day, I’m talking like 15 years plus, it’s still very top of mind, which is pricing is the single biggest lever when it comes to revenue and profits. It absolutely isn’t. Right?

You know, pricing, typically, well, there’s two elements to this, Vijay. One is pricing improvements always, almost exclusively fall directly to the bottom line. It’s very, very frictionless. I mean, if I build a new feature for my application, and it’s really significant, well, now I have to do a press release. And I have to update my documentation, I have to update my sales team, I have to educate them on how to talk to the customers, which is great. That’s an expense. But if I simply were to raise my price, I might have some small costs associated with communicating a price increase to existing customers. But that’s a really powerful lever because it’s a low-cost lever. The second is that McKinsey has data that shows that roughly a 1% increase in price creates a five to 8% increase in actual profit and unit margins. So it’s really curious to me that organizations are not investing much more in their pricing and packaging. It’s kind of just curious to me.

And then when you’re making your other case, again, well put in terms of like, how are you measuring value and if you’re delivering the right value? So in my mind, the second point that came to me was pricing is a good test to see if you’re delivering the right value or not. Increase the price and customers are still sticking, not complaining a whole lot, and not churning. That means you’re, first of all, leaving less money on the table. And the second is customers still see a lot of value in what you’re delivering. Right? Right? Yes, for sure. All right, I know we are coming up against the R, L here, we can go on and on in all these topics.

The last two questions for you are, what resources or communities are people you lean on to stay up to date? In terms of go-to-market practices? Agile, you said Agile community. I can imagine that pricing or even understanding your target customers’ problems, like, how do you stay involved?

You know, it’s funny. I’m not as familiar with any specific communities associated only or exclusively with go-to-market. I tend to think of go-to-market as part of what product management and product marketing do. So I tend to associate with both agile and less agile aspects of product management and product marketing like the Product Development and Management Association is a very classic organization about product management. You see also in the SAFe, the Scaled Agile community, we have a lot of agile product managers from the Agile product management course. And so those are some communities that I stay involved with. And then, of course, there’s LinkedIn, there’s a couple of groups on LinkedIn that are useful. I personally don’t use Facebook. So I am sure there are communities on Facebook. I just don’t participate in those communities. Yep.

And then the final question here is if you were to turn back the clock, what advice would you give to your younger self, granted, you will be happy, and you’ll be satisfied with where you are and how things shape, but if you were to give advice to someone who’s younger in their career.

Well, yeah, it’s funny. We had a dinner party one time, not too long. A couple of months ago, and one of my friends was over, Danny, and he was just eating dinner with us. Like, he said, “What’s the one thing you would change in your life?” And everyone around the table had something they would change, and I had nothing I would change because my life I’ve lived as how I’ve gotten to here. I wouldn’t change anything, the good or the bad. However, there are useful things that, because I do consult with and coach and mentor some young entrepreneurs, right? And so I enjoy that because I was given advice from people, and I think we should pay it forward. So some of the consistent pieces of advice that I like to give to younger people include the idea that you can constantly be learning, and you can constantly be reading and listening to podcasts. Podcasts are marvelous like this because they really do expand our ability to listen, and when you’re driving in your car, why would you waste your time listening to something that doesn’t give you nutritional value? I’d rather you listen to your podcast, right? So I think it’s always about being hungry, staying humble, learning, and growing as generic advice. And now and then very specific advice. It’s staying tuned to the profound technological changes that continue to shape our society and our world. A few years ago, the most profound change was the introduction of the blockchain. Now, Bitcoin and all of the cryptocurrencies aside, blockchain is an important technology, and understanding what that technology is about and its potential uses is important. Another obvious thing that’s going on right now is AI and large language models. And that’s just I think the generic advice to younger people is we all live in very exciting times. And we get stale when we don’t stay current, so do your best to stay current.

Fantastic, lovely conversation. Luke, thank you so much, and good luck to you and the team.

Important Links

-

Check out Luke’s books:

Software Profit Streams(TM): A Guide to Designing a Sustainably Profitable Business

Innovation Games: Creating Breakthrough Products Through Collaborative PlayJourney of the Software Professional: The Sociology of Software Development

Beyond Software Architecture: Creating and Sustaining Winning Solutions

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! http://stratyve.com/